Craftsmen in 18th Century Williamsburg

The Miller in Eighteenth-Century Virginia by Thomas K. Ford and Horace J. Sheely

The good people of Williamsburg, Virginia, have produced a series of booklets on craftsmen operating there during the 18th Century and generously made them publicly available on Project Gutenberg.

While my site is about 18th Century Britain, the technologies in the Old World and the New would have been much the same. I have extracted some of the more relevant material but I urge you to look at the complete publication. Click on the cover illustration to go to the Gutenberg page.

I have extracted the following information about the milling process but there is more information on mills and milling at the Gutenberg link.

The Milling mechanism

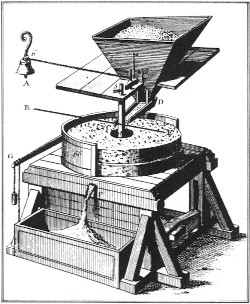

The stones themselves consist of the lower or “bed stone,” which does not move, and the upper or “runner stone,” which turns at a little more than five times the rate of the sails. Its normal speed for best results is 108 revolutions per minute, at which speed it produces five to ten pounds of meal per minute.

The cogs of the brake wheel stay in constant mesh with the staves of a sort of wooden-bird-cage gear called a “wallower.” This is fixed to the upper end of the wrought-iron vertical drive shaft, whose lower end stands in the center or “eye” of the runner stone and turns it.

This simple drive mechanism is complicated by the fact that the runner stone must be held suspended above the bed stone. Ideally, the faces of the two stones—however close together—should never touch. To accomplish this, the runner stone is balanced to turn freely on the point of a spindle that comes up from below through the eye of the bed stone. The spindle, in turn, rests at its lower end in a pivot bearing that can be raised or lowered very slightly by a series of levers.

By this means the miller can adjust the distance between stones according to the kind of grain he is grinding and also according to the speed at which his mill is operating. In a variable wind, for instance, he may have to make the adjustment continuously as the feel of the meal coming from the stone indicates.

The faces of both stones must be “dressed” periodically—perhaps once every ten days when the mill is in constant operation. For this the runner stone must be removed and turned over so that the stone dresser, with his pickaxe-like “millbill,” can operate on both faces. The dresser deepens the furrows, if necessary, and roughens the “lands” between the furrows toward the outer edges of the stones.

When the stones are in good condition, the grain kernels are opened out near the eye of the stones, gradually reduced in the middle area, and the bran scraped and cleaned in the outer one-third of the face. The condition of the bran is the best index of the stone dressing, while the feel of the meal tells the miller whether his mill is running at the best speed and if the stones are set at the proper distance apart.

The difference of a newspaper’s thickness makes the difference between a good grind and a poor one. So for all its clumsiness in appearance and lumbering clatter in operation, the windmill is an extremely precise mechanism at the point where precision counts.